My father was a Navy veteran stationed in East Samar during WWII. He had fond memories of the people he met there, and of their generosity and hospitality.

|

| Philippine Cultural Dancers: Kadena Air Base, Japan. Photo: Senior Airman Nestor Cruz: Wikipedia Commons. |

They also shared their native culture and foods with my father, who was a gregarious butcher by trade, and an amateur chef by avocation, when he could pry my mother out of her kitchen back home.

Many years later, at every holiday family gathering, my father spoke fondly of his time in the Philippines and the wonderful people he met there, entertaining our family with his many stories and memories.

I became curious about our Filipino heritage here in Silicon Valley, when I realized that Guiuan, where my father was stationed, was hit by the recent Typhoon Haiyan and its destructive storm surge, which caused so much devastation in that region.

My father would have been so sad to learn that descendants of the families who were so kind to him when he was so far away from home, had been so impacted by this recent natural tragedy. Likewise, the year before my mother died, she was brought bowls of pancit by visiting Filipino members of her former work community in Northern Silicon Valley. It had become one of her favorite foods from their potlucks at work.

I am dedicating this column to Filipino families in our valley, who are now are suffering such tragic losses and challenges in grieving, locating or aiding their families back home, and who by extension, have been so kind to me and my family, among others they have touched in our community. Their tragedy is our pain, and we will stand by them until their suffering is eased.

------------

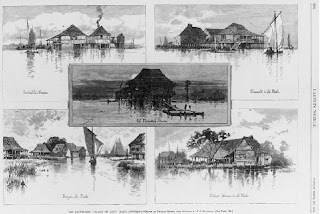

The first permanent settlement of Filipinos in the United States was comprised of

escaped sailors who had been pressed into service on Spanish galleons.

|

| "Manila Village" Barataria Bay, Louisiana: Wikipedia Commons. |

These escapees settled in "Manila Village" Barataria Bay , Louisiana Morro

Bay , California,

Migration to the United States

began after the Spanish-American War, when the Philippines

became a territory of the United States

and Filipinos were exempt from immigration laws.

Many early Filipino residents of California

were agricultural workers, yet some were students (primarily men) sent as

“pensionados,” through a Philippine Commission appointed by President McKinley

in 1901. The commission scholarship program for student

immigration was active between 1903 and WWII.

|

| Filipino American Veterans at the White House, May 2003: Wikipedia Commons. |

During the war the United States Navy recruited Filipinos, who were by that time subject to an immigration quota of only 50 persons per year, due to the Tydings-McDuffie Act, which named them “aliens.”

After the war, The War Brides Act of 1945 and Alien Fiancées and Fiancés Act of 1946, allowed 16,000 Filipina war brides (and one groom) to come to the United States to be married.

Many early nuclear families were located near Navy, Army, and Air Force bases, where some Filipino communities still reside today.

For a wonderful online collection with San Francisco photos of Filipino life in the 1950’s, please

see The Alvarado Project Exhibit: Through My Father’s Eyes.

|

| John C. Gordon Collection: SJSU Special Collections |

Filipinos provided the US with a high proportion of health care professionals, and Filipino nurses were highly sought after by other countries, since there were nursing shortages both in the US and worldwide.

Like many other cultures, Filipino Americans were subject to

early prejudice, which caused them to settle in what were called “Little

Manilas,” communities centered around larger urban cities, which would eventually disperse in later years.

In California , Filipino Americans

intermarried more and clustered less than in other areas of the

country, and seemed to own more businesses.

|

| AWOC/ UFW leaders Larry Itliong & Philip Vera Cruz. Photo by Tim Biley: Wikipedia Commons. |

Some Filipino American agricultural workers were very active in the early farm worker

movement in Northern California .

Larry Itliong and Philip Vera Cruz, co-founders of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), which had already mounted a grape strike in Delano, merged with the National Farm Workers Association founded by Cesar Chavez, whose NFWA group walked the picket line in solidarity with AWOC workers.

The merged group became known as the United Farm Workers Association, whose goals were to increase their impact in achieving a shared vision of equity and respect, and to obtain unemployment insurance for farm workers. UFWA later evolved into a farm workers’ union under the AFL-CIO, and was renamed the United Farmworkers Union.

Larry Itliong and Philip Vera Cruz, co-founders of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), which had already mounted a grape strike in Delano, merged with the National Farm Workers Association founded by Cesar Chavez, whose NFWA group walked the picket line in solidarity with AWOC workers.

The merged group became known as the United Farm Workers Association, whose goals were to increase their impact in achieving a shared vision of equity and respect, and to obtain unemployment insurance for farm workers. UFWA later evolved into a farm workers’ union under the AFL-CIO, and was renamed the United Farmworkers Union.

Likewise, Filipino Americans are the second-largest Asian

American group in the United States

(after Chinese Americans) and generally enjoy a longer life expectancy than

most other Americans.

|

| Bay Area, Señior Sisig Filipino Fusion Truck. Esque Magazine: Wikipedia Commons. |

In contrast, the entire San Francisco Bay area (San Francisco and Oakland, South to Fremont) has 287, 879 Filipino residents among 4,335,391 total residents, or 6.64% of the total population in this region.

According to the 2002 US Economic census, Filipino-owned businesses are primarily in the medical, dental and optical fields, and include Filipino-owned restaurants. In Northern California most of these businesses are located in the Bay Area, with Santa Clara County now home to the largest Filipino community in Northern California. (Los Angeles has the largest population of Filipino Americans in Southern California .)

|

| Lloyd LaCuesta, Image: Courtesy of KTVU |

Notable Bay Area Filipinos include:

Lloyd LaCuesta – KTVU television journalist and South Bay bureau chief

Diosdado Banatao – Engineer, philanthropist and businessman

|

| Rob Bonta, ASMDC.org |

|

| Jose Esteves, City of Milpitas |

Rob Bonta (Left) – The first Filipino American California State Legislator

Jose Esteves (Right) – Mayor of Milpitas and former city councilman

The Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS) Santa Clara Valley Chapter has more information on the history of local Filipino Americans in our valley.

The Filipino AmericanChamber of Commerce of Santa Clara County also has resources for tapping the wealth of experience in the Filipino community of Silicon Valley.

------------

To contribute funds to Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda) flood relief efforts in the Philippines, please see the list of relief organizations vetted as credible by APALA, the Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance of the AFL-CIO: http://apalanet.org/apala-blog/yolanda/